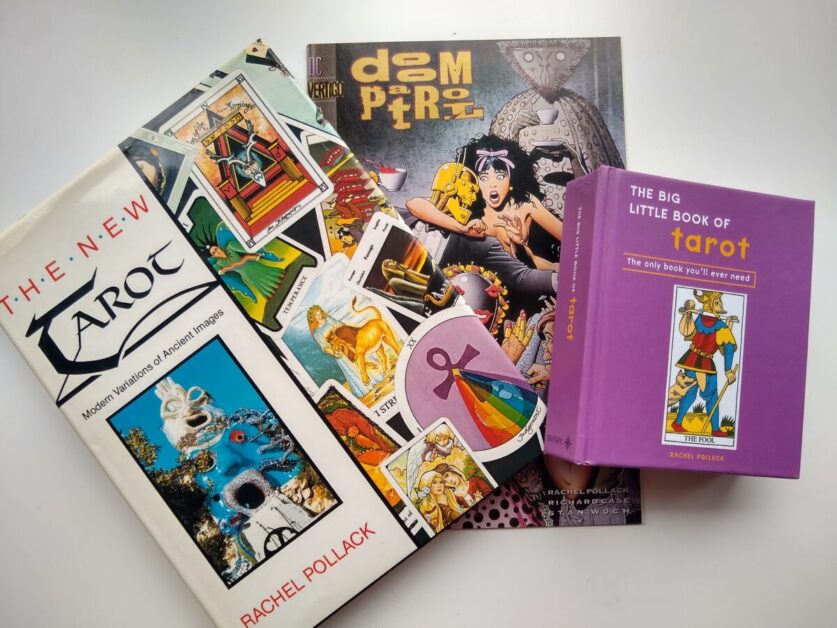

Rachel Pollack is a trans icon, science fiction author, tarot historian and deck designer. She wrote one of the seminal works on the art of modern tarot reading, The 78 Degrees of Wisdom, and even found time to write for the comic Doom Patrol.

Rachel Pollack is a trans icon, science fiction author, tarot historian and deck designer. She wrote one of the seminal works on the art of modern tarot reading, The 78 Degrees of Wisdom, and even found time to write for the comic Doom Patrol.

Our sessional worker Raphaël interviewed Rachel for the March edition of our monthly newsletter for trans and non-binary people: T Monthly.

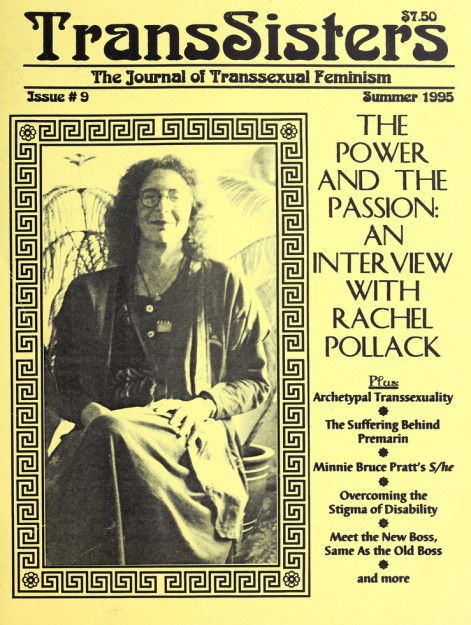

She generously talks to us about her experiences of coming out as trans and lesbian in the early 1970s, and shares her perspective on the power of being queer.

T Monthly: Have you ever been to Scotland?

Rachel: Yes, my friend and I were there, several years ago now. We just love the whole place. We spent a lot of time in the highlands, we also went to Edinburgh, Glasgow, and just had a great time.

T Monthly: You transitioned fifty years ago. Do you still think about your own gender?

Rachel: Yeah. Because it’s something that’s a very basic part of who I am. I had this realization that in the year 1971, my whole life changed. I discovered the tarot – the tarot discovered me as I like to say – I sold my first professional story, and I came out as trans and lesbian. And all in that one year, so it was just an amazing year. And in some ways, all those things keep reverberating through my life.

One of the things I’ve tried to contribute over the years is to see being trans, being queer in general, trans in particular, as this really great experience, as an amazing thing that most people don’t get to have any knowledge of, and I always think that’s a valuable thing

T Monthly: And how did it come to you, that transitioning was a possibility?

Rachel: Well… it wasn’t in a certain sense. I mean, I kind of made my own path, I really didn’t know what there was out in the world. I did know because I had this constant thing going on in my head. It was really focused, condensed, you might say, as I think it is for a lot of transwomen, somewhat on clothing and appearance. And wanting to dress as a woman and be acknowledged in some ways as a woman. I kept this buried, not from consciousness but from any expression other than in very private moments when I would allow myself to go there. But it was really affecting my life. I was in my early twenties, and it was one of those situations for me as for many trans women, at least back then, that I had no words for my feelings. People in those days tended to assume that a desire to cross-dress was somehow an aspect of being gay. But I was not attracted to men. So in a certain sense I just didn’t know what, or who, I was. And there were no models back then. I guess I knew of Christine Jorgensen who was a very famous “sex change” person from the fifties. But that was always done in such a salacious way. And I did not really feel a connection there, either, because it was all about surgery, and that too was not who I was.

And then I married this wonderful woman I was first friends with and then in love with. And I figured – like a lot of trans women at that time did, oh well now that I’m in a stable, permanent relationship then all the other stuff will just go away. And of course it was just the opposite. I felt this intense pressure. Within three months I had to tell her, I had no way not to tell her that I had these feelings, and she freaked out. I understand that completely. Even more than me, she had no experience, no cultural models, to help her deal with that shock.

And then it was the Autumn of 1970, and I was teaching at a college. I hung out with the students because they were so much more fun than the faculty. And so I was at someone’s house and we were all stoned. I think I must have had a very mild acid trip. I remember going off by myself and feeling this thing in the back of my head kind of gnawing at me, and wanting to come forward. And I realised that my great fear was that I wanted to be a woman. And I said ok so I’m going to have to open this up and just look at it. And as soon as I did that, this overwhelming truth came out – I am a woman. No wanting was involved, this is who I was, in a very fundamental way that had nothing to do with anything else. And I came out and I said to my friend, I’m a woman.

And this, strangely, was something she could grasp. Partly it was because she’d gone strongly into the women’s movement, and the idea of self-determination, and not obeying society’s rules of who you are.

From there, I just went completely into it. At the same time I simply ignored the whole medical pathway. I was just being myself and having a wonderful time. But then I wanted to get hormones, and I really had no idea how you were supposed to do that.

T Monthly: Was there a gender clinic where you were at that time?

Rachel: Oh yeah, it was a horrible one though. The Doctor was a real bastard. I never met him, happily, but an awful person, he was actually notorious in the community. He did things like, one of the women that I knew who had been in that program, she had a good career as an engineer, and she was told that in order to be ok for surgery, she had to quit her job, and get a job being a clerk in Woolworth because that was a woman’s job. He was a tyrant, he just totally controlled these women’s lives. But I had no idea that was going on, and I had no idea that you got hormones to transition by saying your goal was surgery. Because my goal wasn’t surgery, I wasn’t thinking about that at the time. So I just went to this doctor who did hormones and I thought, well, the only other word besides transsexual was transvestite. So I said I was a transvestite and I wanted oestrogen. He said “OK”. And the reason he did that was because in their strange little minds transvestites were sick people who had fetishes and what you did with that was you gave them oestrogen to damp down their desires. And therefore they’d stop feeling those feelings. That’s what he would have done even if I hadn’t asked for hormones, he would have prescribed hormones.

Rachel: Oh yeah, it was a horrible one though. The Doctor was a real bastard. I never met him, happily, but an awful person, he was actually notorious in the community. He did things like, one of the women that I knew who had been in that program, she had a good career as an engineer, and she was told that in order to be ok for surgery, she had to quit her job, and get a job being a clerk in Woolworth because that was a woman’s job. He was a tyrant, he just totally controlled these women’s lives. But I had no idea that was going on, and I had no idea that you got hormones to transition by saying your goal was surgery. Because my goal wasn’t surgery, I wasn’t thinking about that at the time. So I just went to this doctor who did hormones and I thought, well, the only other word besides transsexual was transvestite. So I said I was a transvestite and I wanted oestrogen. He said “OK”. And the reason he did that was because in their strange little minds transvestites were sick people who had fetishes and what you did with that was you gave them oestrogen to damp down their desires. And therefore they’d stop feeling those feelings. That’s what he would have done even if I hadn’t asked for hormones, he would have prescribed hormones.

So of course when I started developing breasts it was a wonderful thing and just totally reinforced everything in my life. I felt like that was what I was meant to do. Then some years later I decided I wanted surgery. I was lucky there too, because I was in Holland and in Holland they did not have this tyrannical situation. There was a surgeon, and then there was a psychiatrist, and I had to go get his permission. Looking back on people I’d known who had had such a hard time, I thought oh my god, what’s he going to make me do? Because I didn’t want surgery until I wanted it, but as soon as I wanted it, I really really wanted it. I didn’t want to wait one day.

So I went to see him, and I knew him because I was in a support group that he officially monitored, so I talked to him and he said, “well you obviously know yourself better than I do, and you know what you’re getting into, so that’s fine. I will give permission.” My entire time with the psychiatrist was twenty minutes.

T Monthly: Do you think things seem easier now?

Rachel: I’m so happy that kids are getting to transition or at least experiment, I think that’s so valuable. But still, I find that the medical profession is such a tight model of how you have to be to be able to do those things. And it’s so narrow. You have to be heterosexual in your chosen gender. You have to have all the role behaviour, like transgender girls have to play with dolls and play house and all that stuff, you know, and have to do this from the very beginning. You can’t bury it, or try to hide it. If you bury it, they won’t approve you. In reality a lot of trans people I’ve met don’t fit those models. If you’re a child, the only way you’ll get any recognition or help is to fit that rather rigid model of masculine and feminine which is really a shame.

But the big thing that’s changed, an astonishing change, is that transgender people are now visible. Society recognizes that this is something people can be. Obviously, there is a strong reactionary element fighting change, as always, but the difference is remarkable.

Back in my time, because it was so early, everyone was defined as sick, being trans was a sickness. And the general medical model was well these people can’t be cured so we’ll just have to in a sense humour them. So they can have something like a happy life. That was the basic idea.

In the 90s I moved back to the States (I was living in Holland), and I started doing some spiritual studies. And discovering that there were trans people all through human history, which is so wonderful, everywhere in the world too, I started seeing that the alternative – the way not to be sick, is not to say I’m not sick I’m ok. Because that’s negative, and you can never fight against an ingrained belief that’s been given to you by society just by saying, no, I’m not sick, I’m fine. The way to overcome sickness is to have power, to see that what you’re doing is a great thing. And that it’s worldwide, and as old as humanity.

At that time I became enamoured with the Tao Te Ching from China. And in the translation I had at the time, chapter 71, let me see if I can remember it now, I think it’s something like, knowing ignorance is strength, ignoring knowledge is sickness. If one is sick of sickness, one is not sick. The sage is sick of sickness, therefore he is not sick. And this really reverberated for me on many levels. Knowing ignorance is strength. This is really an important point. Because everyone kept asking what causes [people to be transgender]. What causes a person to be this way.

So I took the sense, maybe there is no cause, maybe it’s one of the ways people are, and it’s a dead end to worry about what caused you to be yourself. And so to know that you’re ignorant of how you became who you are is a great strength because it releases you from pursuing that fantasy – that something made you the way you are, something your mother did, hormones in the womb, bla bla bla, society’s pressures… But then, ignoring knowledge is sickness, and to me that was about ignoring all the knowledge of transgender people through history and all across the world. If you ignore that, it will almost certainly make you sick. And then, the way to stop being sick, is to be sick of sickness. To say to yourself—and really mean it–I am not sick, I’m not going to see myself like that, I’m sick of it, I’m done with it. So that was the path I took and, I did a lot of writing about transgender figures in mythology.

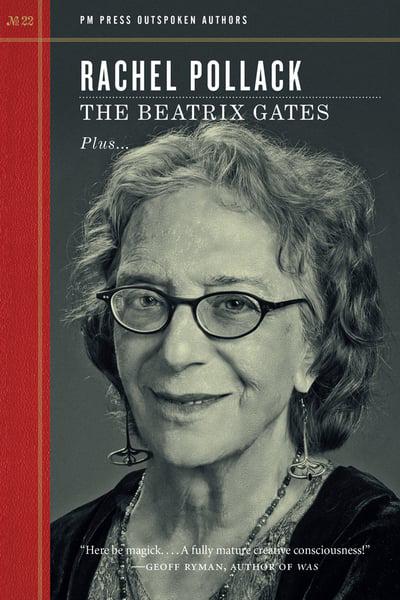

T Monthly: Can you tell us about the most recent book you published?

Rachel: The Beatrix Gates – It’s a collection of a couple stories of mine, one of which is very much a transgender story, and an essay called Trans Central Station, about the early days for me and growing up. It’s an essay I’m very proud of. There was also an an interview with me, by the editor of a series – the series was basically all the science fiction writers who are not as well-known now. It was a great interview, I really enjoyed it.

Rachel: The Beatrix Gates – It’s a collection of a couple stories of mine, one of which is very much a transgender story, and an essay called Trans Central Station, about the early days for me and growing up. It’s an essay I’m very proud of. There was also an an interview with me, by the editor of a series – the series was basically all the science fiction writers who are not as well-known now. It was a great interview, I really enjoyed it.

At the end he said “So Rachel were you ever a nice Jewish boy?” (a cliché American expression in the 50s-60s). I said “Well, I’ve always been Jewish even when I thought I wasn’t, and I’ve never been a boy even when I thought I was… And I’ve always tried to be nice. I’ve also always tried to be tough.” That was my answer.

Rachel’s most recent book is The Beatrix Gates, a collection of essays and short stories, is published by PM Press.