Miss Major Griffin Gracy: trans woman and trans activist of colour

By Siobhan Donegan

Miss Major Griffin Gracy is a trans woman of color, whom for the purposes of brevity I shall sometimes refer to simply as Miss Griffin, or Miss Major. Miss Griffin is also an important figure in trans activism. Her activist work has made an important and significant contribution to identifying the root causes of gender discrimination, particularly of trans women of color. In Griffin’s opinion it is the ‘prison industrial complex’ that is a major factor in the incarceration of trans women of color and of other people of various queer identities.

Miss Griffin has pointed out that transgender or genderqueer is a perspective or state of being which is ‘outside of the law’, despite the fact that there are of course many transgender people who are not imprisoned. What she means here, is in reference to the experience of ‘constant rejection’ from the mainstream heteronormative society, particularly in the pursuit of education or employment.

Because there are a large percentage of trans women of color facing race and ‘gender based’ discrimination, many of them expect to die young – as there has been and still is an ‘epidemic’ of murders. As such, the term ‘Black Transgender Elder’ remains unusual and to some unthinkable, however this is precisely what Miss Major is. She is considered to be an icon as has been described as having shaped the trans rights movement.

Miss Major is a ‘veteran’ of the historic Stonewall riots, and she also survived the Attica State Prison. In this context, the struggle of the LGBT community for equality ‘intersects’ with Miss Major’s personal activism for transgender civil rights. Griffin’s career, pioneering for social justice, extends over 50 years.

Miss Griffin Gracy was born on October 25th 1940, in the South side of Chicago, and was assigned male at birth. It was around about the age of 15-16 that she first discovered that she liked wearing female clothes. At this young age, Miss Griffin began to experiment by trying on her mother’s clothes. Unfortunately, Griffin’s mother found out which resulted in her getting a beating. She then started meeting up with friends that she describes as ‘little’ drag queens.

Miss Major, at the initial stage of her transition, had to depend on the black market for her hormones. She turned to sex work and illegal activities such as theft in order to survive. Miss Major was just 22 when she moved to New York City. She already knew that there was a thriving trans community on 42nd street, and thus this is where she found an apartment.

Miss Major reflected that during the era of the 1960s, many people didn’t realise that they were questioning or exploring their gender identity, specifically their gender assigned at birth. Back then the contemporary terminology related to gender identities simply didn’t exist.

It was the murder of Griffin’s friend known as ‘Puppy’, a Puerto Rican trans woman and sex worker whose body was found in her apartment, that acted as the catalyst to Griffin becoming involved in trans activism. The authorities had ruled the case as a suicide despite Griffin’s belief that there was evidence for murder. This event increased her awareness of the uncaring attitude of authorities to the number of young trans women being murdered.

As mentioned, Miss Griffin was a veteran of the Stonewall riots, and her friends from that important era are now famous icons such as Marsha P. Johnson, Crystal La-Beija and Sylvia Rivera. During this time, Miss Griffin was a regular of the Stonewall Inn. Unfortunately during the first night of the Stonewall riots, she had her jaw broken by a police officer and was subsequently knocked unconscious, previously having been taken into police custody. However, there are contradictory evidence, as one version of this story says that it was a correction officer who broke Miss Griffin’s jaw after being taken into custody.

During her youth, Miss Major also participated and experienced the splendour of the ‘Drag Ball scene’. During an interview in 1998 she described this wonderful scene: “The Drag Balls were phenomenal! It was like going to the Oscars shows today. Everybody dressed up. Guys in tuxedos, Queens in gowns you would not believe!”. Anecdotally, some of the competing Queens had been working on their ‘gowns’ all year long.

Returning to the harsher elements of Miss Major’s story, she was in fact incarcerated for five years. Upon her release from prison in the late 1970s, she moved to California to continue her activism.

During the AIDS epidemic, Miss Major worked with several HIV/AIDS organisations based in the San Francisco area. During the early 1980s, she focused her commitment directly on helping people with HIV/AIDS – she even drove San Francisco’s first mobile needle exchange.

After facing many personal hardships in her life, including homelessness and imprisonment, Miss Major, who is also sometimes known popularly as ‘Mama’, became a vocal activist for trans rights. In 2005, she joined Trans Gender Variant and Intersex Justice, initially as a staff organiser progressing to become the Executive Director. Miss Major often spoke out against the prison system in America, and as the executive director focused the group’s attention on the imprisonment of trans women, particularly trans women of colour.

After facing many personal hardships in her life, including homelessness and imprisonment, Miss Major, who is also sometimes known popularly as ‘Mama’, became a vocal activist for trans rights. In 2005, she joined Trans Gender Variant and Intersex Justice, initially as a staff organiser progressing to become the Executive Director. Miss Major often spoke out against the prison system in America, and as the executive director focused the group’s attention on the imprisonment of trans women, particularly trans women of colour.

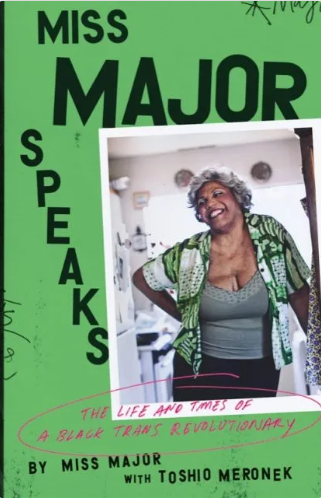

There is a biographical book called ‘Miss Major Speaks – The Life and Legacy of a Black Trans Revolutionary’ co-written by Miss Major herself and Toshio Menorek. In this work, Miss Major speaks of her survival of the Bellevue Psychiatric hospital, Attica Prison and the AIDS crisis. The book is perceived as a ‘roadmap’ for black, trans and queer youth on ‘their path to liberation’, even though as Griffin herself reflects, the experience of trans people today is different.